The Pedagogical Impact of Digital Technologies in Classrooms

Impact Project Collaboration Between Kennisnet and Dr. Niels Kerssens

Earlier this year, I met with Dr. Niels Kerssens, Assistant Professor in the Department of Media and Culture Studies at Utrecht University, to trace the trajectory of his Impact Voucher-funded project. Our conversation moved in stages, beginning with the contours of the project, then what set it in motion, the “why” behind it – including both its relevance and the value of cross-sector collaboration – and finally some reflections on where it will lead.

This Impact project, focused on the pedagogical impact of digital technologies in classrooms, is a collaboration between Kennisnet, the Dutch public organisation that supports primary, secondary, and vocational education in their use of ICT, and Niels, whose research to date has examined the platformisation of education and the future of digital autonomy in European schooling.

The project is guided by three main questions:

- What is the pedagogical impact of digital technologies in classrooms?

- How can schools embed digital tools in ways that are pedagogically meaningful, value-aligned, and educationally significant?

- How might education be organised around logics other than those of platforms, and what role might this project play in that process?

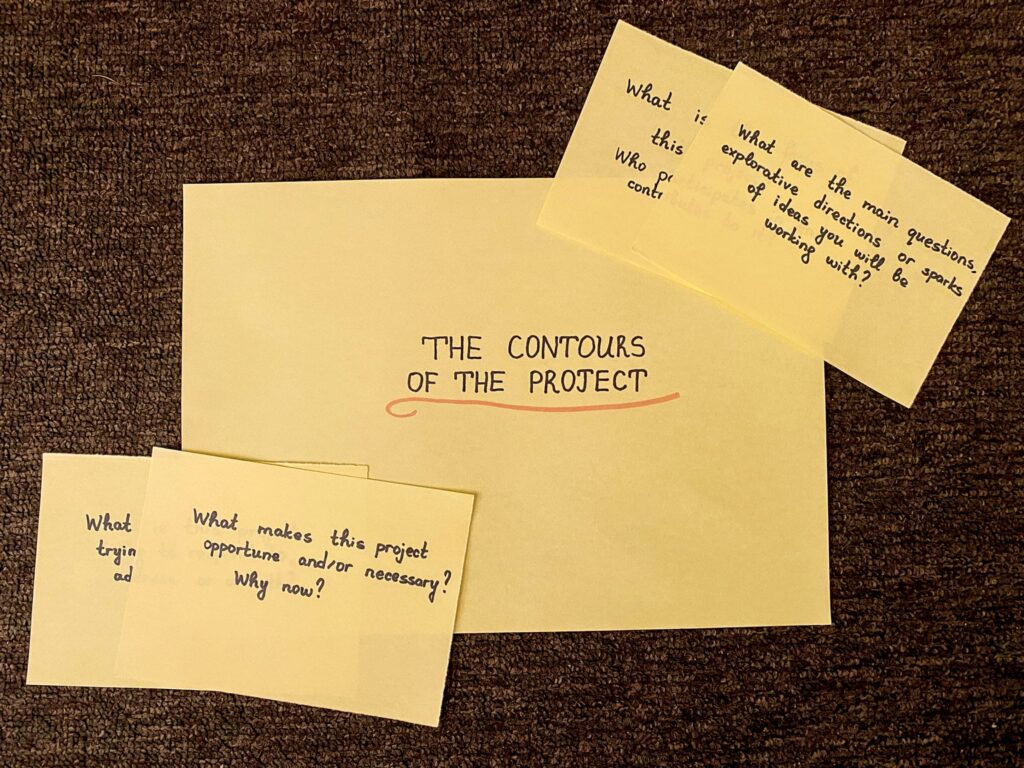

The Contours of the Project

At the heart of the project is the PIO Tool (het Pedagogisch Impact Onderzoek in Dutch, the Pedagogical Impact Assessment in English), a practical resource consisting of cards with questions developed in collaboration with Kennisnet for use in primary and secondary schools. Its purpose is to bring stakeholders together in structured dialogue about the pedagogical impact of digital technologies.

Methodologically, the PIO Tool takes inspiration from Data School’s De Ethische Data Assistent (DEDA) tool. Conceptually, it builds on Catherine Adams and Sean Groten’s TechnoEthical Framework for Teachers, created to “aid educators in selecting and employing educational technologies in ethically sound and pedagogically sensitive ways in their classrooms” (2023, 701).

Inspired by these frameworks and adapted to the Dutch educational context, the PIO Tool encourages reflection on three core pillars, including power and control, children’s rights, and the evolvement of the child in classroom environments. These pillars intersect with the growing presence of digital technologies in schools and are meant to spark reflection among stakeholders in their own educational contexts, asking what technologies actually do when they encounter classrooms, pedagogies, and teacher-student dynamics, beyond the intended affordances of the tools themselves.

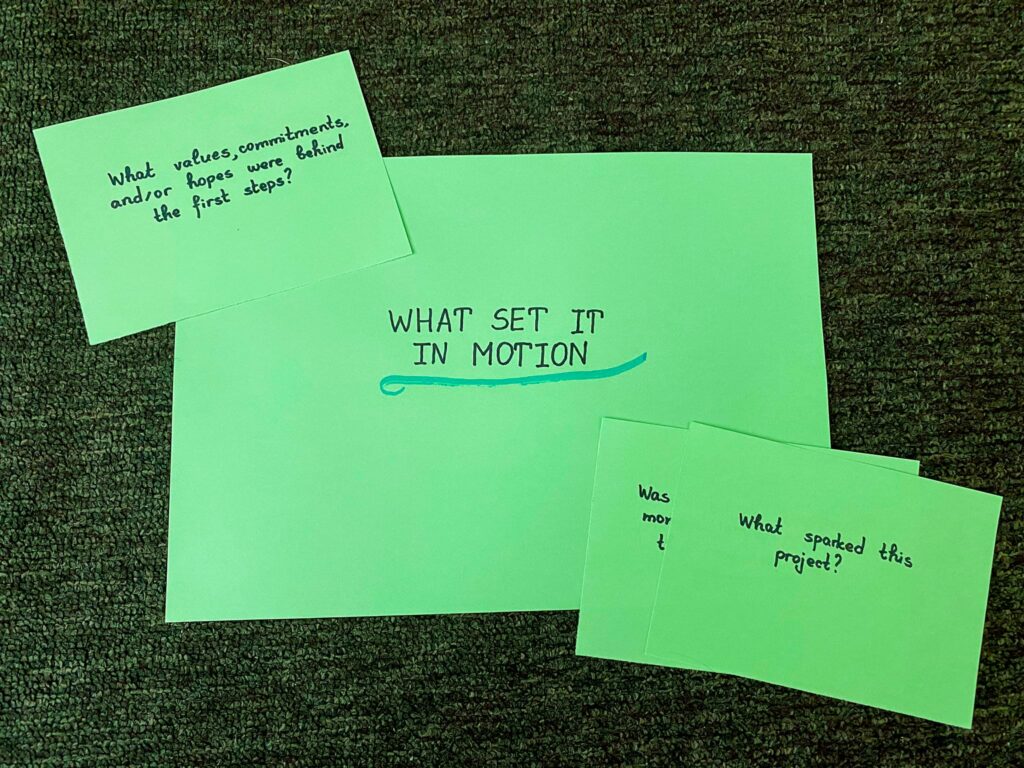

What Set It in Motion?

The project developed from Niels’ NWO Veni project (2021-2024) titled “Platformisation of Primary Education: Public Values at Risk,” which examined how platform logics reshape education as a public good. That research focused on public values, such as professional teacher autonomy in decision-making, as well as justice, humanity, and privacy.

Although the NWO Veni project also considered the pedagogical impact of digital technologies, its emphasis was on the risks these technologies pose for public values. The Impact Voucher project shifts attention toward creating opportunities for reflection. As Niels observed, the pace of digitalization in schools is so rapid that stakeholders rarely have time to consider its implications for pedagogy, classroom dynamics, or teacher-student relationships. The PIO Tool was designed to open up this reflective space.

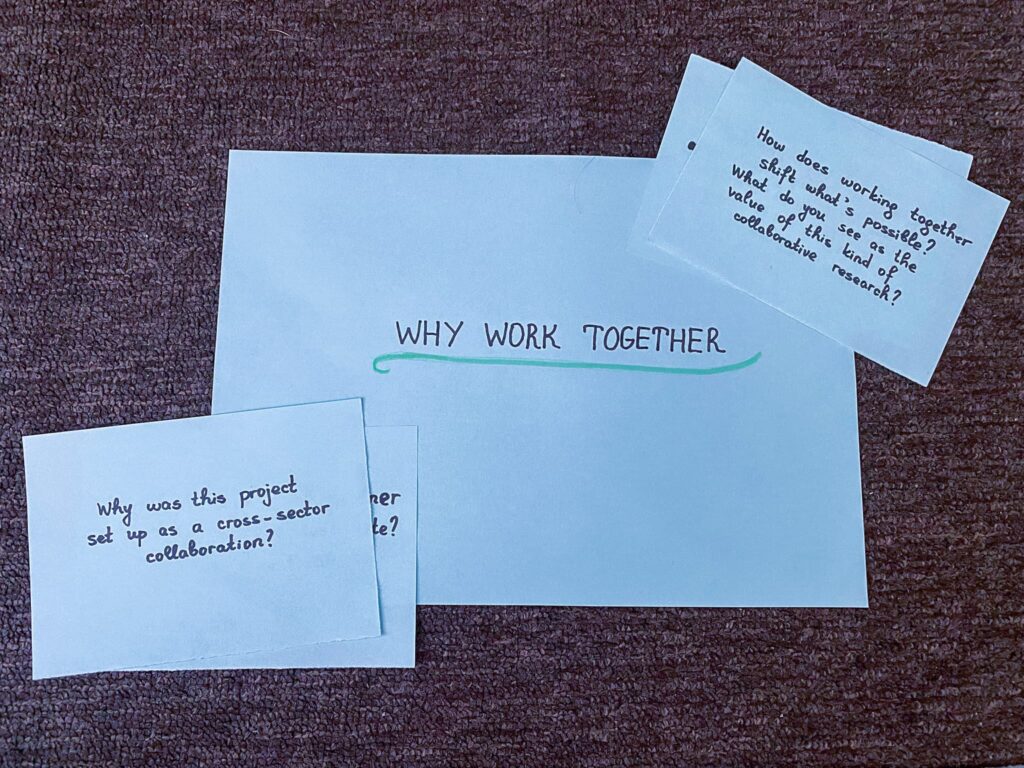

Why Work Together? What is the Hoped-For Change?

When asked why cross-sector collaboration is necessary, Niels was clear that at the intersection of digital technologies and education it is not optional but fundamental. A researcher may succeed in developing a tool, yet for that tool to have impact on those it is intended for, external partners such as Kennisnet are indispensable. They provide access to schools and create the situated conditions in which a tool can be tested and adapted. Once within those situated contexts, the work is no longer a one-directional transfer of knowledge but becomes a process of mutual, hands-on learning with and from each other. Researchers and practitioners can observe together how digital technologies function in classrooms, critically reflect on their pedagogical consequences, and consider how they might be embedded in curricula with greater sensitivity and care, guided by educational and socially-desirable visions rather than purely technological ones.

Such collaboration also makes continuity possible. The reflective, critical mindset cultivated through the tool can extend into other domains, for example, through teacher education courses or train-the-trainer programmes that allow for broader uptake across school contexts. In this way, the project is not confined to in situ encounters with the tool but has the potential to influence pedagogical practice more widely.

Finally, working in partnership with public sector organisations further makes it possible for innovations to move beyond the horizons of individual schools. While the initial effects may be local and situated within a specific classroom or a teaching team, the tool can scale when adopted by institutions more broadly. This opens the possibility of national influence and, in time, contributions to wider European debates on the pedagogical influence of digital technologies in classroom environments.

As Niels himself remarked:

“This is another opportunity to engage in conversation, but also bring other people to the table who were not there previously. For me, collaborating with partners outside academia is genuinely energizing.”

Niels Kerssens

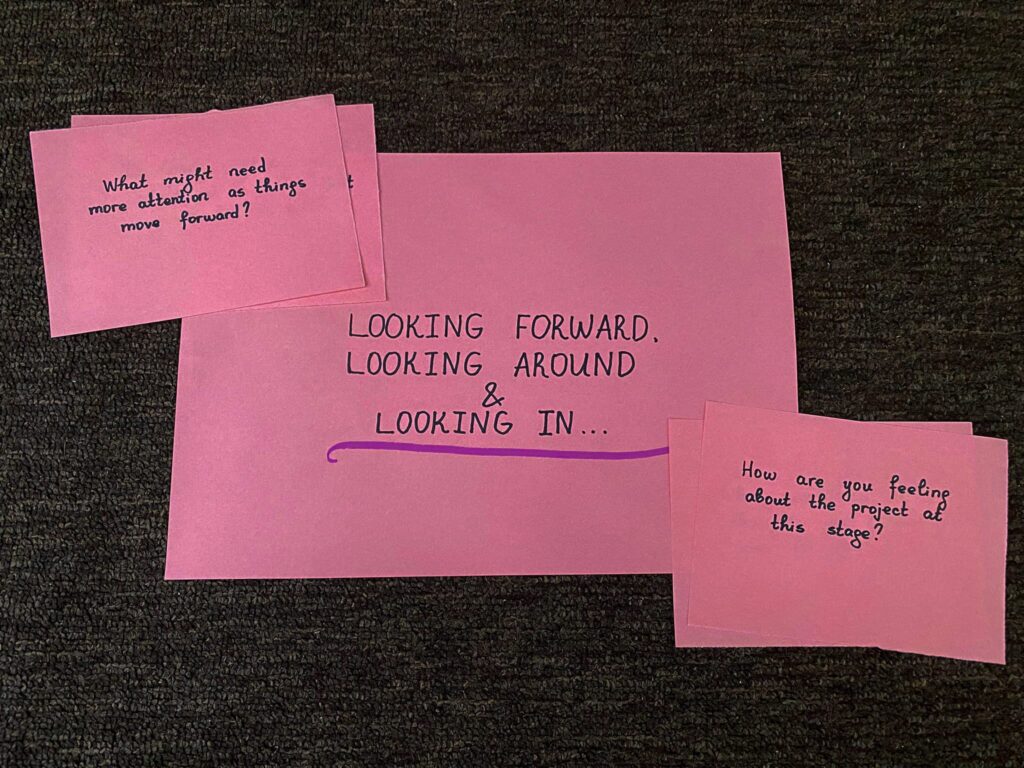

Looking Forward, Looking Around & Looking In

One point Niels emphasized in our conversation was how many educational stakeholders perceive digital technologies in a narrowly instrumental way. They are often seen as means to achieve specific ends, such as boosting learning outcomes, meeting performance targets, or fostering a positive classroom climate. Yet this perspective, as he emphasized, risks overlooking other dimensions of impact, including how technologies reshape teacher-student relations, how they can reinforce existing biases, and how they may, subtly or not so subtly, encroach upon the pedagogical space itself. The pressing question, then, is how to move beyond this instrumental barrier and create room to think more holistically about what technologies are doing in classrooms.

The next steps focus on testing and refinement. Pilot versions of the PIO tool will be trialled in classroom environments in collaboration with Dutch teacher training colleges. Researchers working with teacher teams will explore what functions well, what does not, and how the tool might be improved, as well as how the initiated conversations can be translated into concrete actions and incorporated into the educational institution’s decision-making. Beyond these pilots, there is the ambition to link up with European projects working on related issues. At present, such initiatives remain fragmented: some concentrate on evaluating EdTech, others on pedagogy, ethical embedding, or co-design processes aimed at making educational technologies more democratic. The goal is to begin building a European network around tools of this kind, allowing educational institutions worldwide to reflect on and evaluate the impacts of the technologies being introduced into their classroom environments.

Finally, a related symposium – resonating with the Impact Project and the PIO Tool’s focus on the intersection of EdTech with pedagogical, ethical, and value-based questions – will take place in Utrecht in December 2025, co-organized by Niels and financially supported through the Impact Voucher funding. Over two days, the symposium will bring together leading research and practice initiatives, offering a space for participants to collectively address critical challenges around value-driven design, implementation, and assessment of EdTech, grounded in ethical, pedagogical, and environmental commitments. This symposium will create an opportunity for these initiatives, as well as key stakeholders from public education, to cross-pollinate ideas, spark collaborations, and lay the groundwork for invigorating their collective capacity to develop meaningful alternatives and build robust, democratic structures for digital self-governance and EdTech oversight.

I would like to thank Niels for taking the time to speak with me, and I invite you to keep an eye on Data School’s website and LinkedIn for updates on upcoming events, emerging insights, and the progression of this Impact Project.

References

Adams, Catherine, and Sean Groten. 2023. “A TechnoEthical Framework for Teachers.” Learning, Media and Technology 49(4): 701–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2023.2280058.